You see the headline everywhere: “EV Battery Warranty: 8 years or 100,000 miles.” It creates a mental image—at 100,001 miles, the battery tragically dies, and the entire car is rendered useless, destined for the crusher. This is the “cliff-edge” myth, and it’s fueling anxiety about electric vehicle waste. But the reality is far more interesting, and far more sustainable.

An EV battery doesn’t die like a lightbulb. It degrades, slowly losing its ability to hold a full charge. When it can only hold 70-80% of its original capacity, it’s no longer ideal for the demanding job of propelling a two-ton vehicle 300 miles. But with 70% of a massive, engineered, and incredibly valuable battery pack still perfectly functional, its life is far from over. We’re entering the era of the “second-life battery,” where an EV’s retirement is just a career change. Let’s follow the battery’s journey from the road to your home.

Part 1: The “Retirement” – When is a Battery Too Old for the Road?

First, let’s define “end of life” for an automotive battery. It’s not a failure; it’s a performance threshold.

- The Rule of Thumb: Most automakers consider a battery eligible for warranty replacement when it falls below 70% of its original State of Health (SoH). This typically takes far longer than the warranty period for most drivers.

- The Reality: A battery at 70-80% SoH is still a phenomenal energy storage unit. It just can’t deliver the peak performance and range required for a primary vehicle. This is where the second-life concept begins. Instead of being recycled immediately (which is energy-intensive), we can repurpose it for less demanding jobs.

Part 2: The “Second Career” – A World of Stationary Storage

Once removed from the car, these battery packs are tested, re-configured, and given a new, slower-paced job: stationary energy storage. Here’s where they shine:

Application 1: The Grid-Scale “Buffer”

Imagine a warehouse filled with hundreds of repurposed EV battery modules. This becomes a Grid-Scale Battery Energy Storage System (BESS).

- What it does: Stores cheap, abundant renewable energy (from solar farms or wind turbines) when it’s being produced and releases it to the grid during peak demand hours.

- The benefit: It smooths out the intermittent nature of renewables, makes the grid more resilient, and reduces reliance on polluting “peaker” power plants. Companies like B2U Storage in California are already doing this at scale.

Application 2: The Commercial & Industrial Power Manager

Factories, data centers, and big-box stores have huge, fluctuating energy demands.

- What it does: A second-life battery system can be installed on-site to perform “peak shaving”—drawing power from the battery during expensive peak-rate hours instead of the grid, slashing electricity bills.

- The benefit: Significant cost savings and a smaller carbon footprint for businesses.

Application 3: The Home Energy Hub

This is the most personal application. Imagine your home’s solar panels charging a battery bank in your garage during the day, and that bank powering your home at night.

- What it does: A second-life home storage system (like those pioneered by companies in Europe) allows for greater energy independence. It can also provide backup power during outages.

- The benefit: Maximizes your use of self-generated solar power, reduces grid dependence, and provides security. It’s a more affordable entry point than a brand-new home battery (like a Tesla Powerwall).

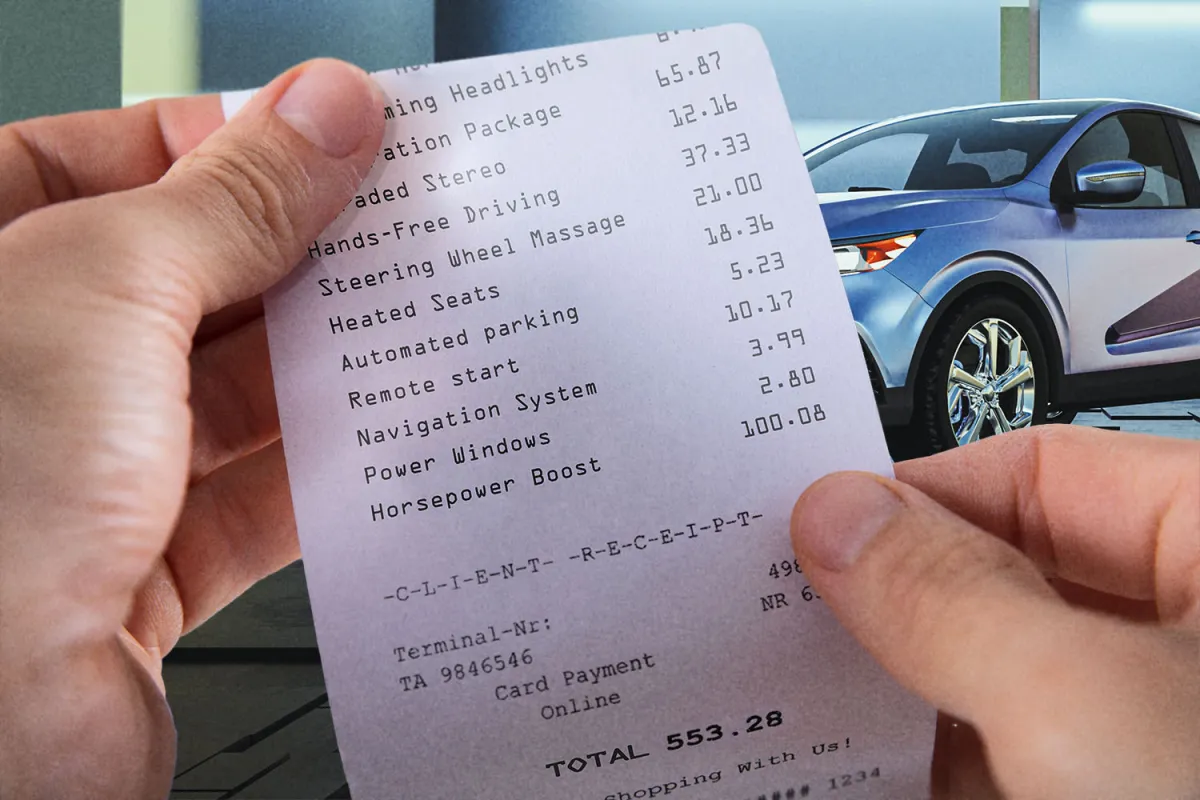

Part 3: The Economics & Logistics: Making the Circle Work

For second-life to become mainstream, a viable ecosystem needs to exist.

- The Collection & Assessment Hurdle: Automakers and a new breed of “battery health” diagnostic companies need to create systems to efficiently collect, transport, and assess the State of Health of used packs. Standardization is key.

- The “Dismantling & Reconfiguration” Challenge: An EV battery pack is a complex assembly of modules and cells. Safely dismantling it and reconfigging modules into a new, stable stationary pack requires specialized facilities and expertise.

- The Economics: It must be cheaper to repurpose a battery than to recycle it for raw materials and cheaper than buying new storage cells. As the flood of first-generation EVs (Nissan Leafs, early Teslas, etc.) now reach retirement age, the scale is making this economics work.

Part 4: The Final Chapter: When Recycling is the Right Answer

Even second-life batteries won’t last forever. After 10-15 years in stationary storage, they will eventually degrade to the point where repurposing is no longer viable. Then, the final stage begins: advanced recycling.

- The Goal: To recover the valuable raw materials—lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese—at purities high enough to go straight back into new battery production. This is called “closed-loop” or “circular” recycling.

- The Technology: New processes like hydrometallurgy and direct recycling are emerging to do this more cleanly and efficiently than simply smelting the packs.

- The Vision: A true circular economy where an EV battery is used in a car → repurposed for storage → recycled into a new battery, dramatically reducing the need for environmentally damaging mining.

Conclusion: From Linear Grave to Circular Life

The narrative of the “dead EV battery” is a relic of a linear, throwaway mindset. The future is circular. An EV battery is not a consumable; it’s a long-life capital asset with a multi-decade, multi-career journey.

This changes the entire environmental and economic equation of electric vehicles. It turns the battery from a potential liability into a long-term store of value—first for mobility, then for grid stability, and finally as a repository of critical minerals.

So, the next time you see an old Nissan Leaf, don’t see a clunky early EV. See a future power plant. See a backup for a hospital. See the heart of a sustainable home. Its first life is just the beginning of a much longer story—one that powers not just cars, but our cleaner, more resilient energy future.